This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I'm Dr Matthew Watto, here with America's primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, are you ready to talk about some adrenal insufficiency? We had a great conversation with Dr Kargi, and I'd like you to start us off.

Paul N. Williams, MD: How about thinking about it? It's a good place to start.

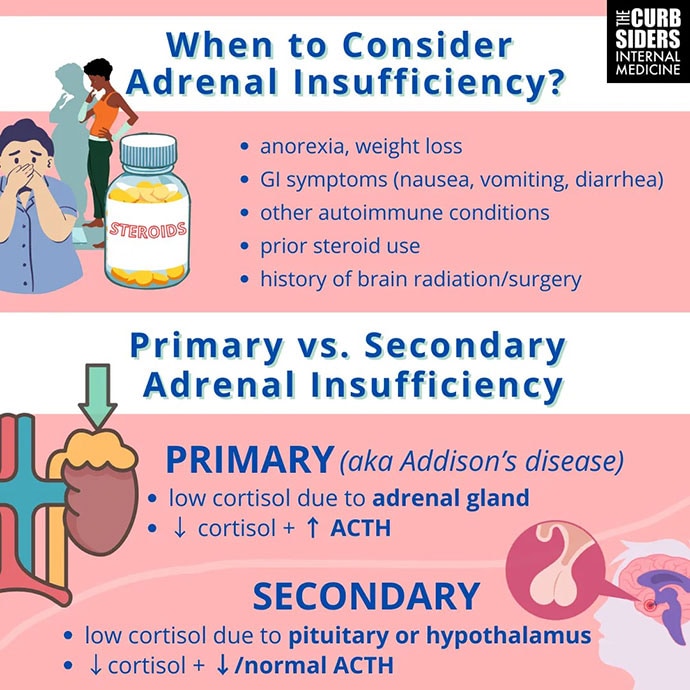

That's one of the ways this episode changed my approach a little bit. I never really thought about the fact that many patients present for evaluation of adrenal insufficiency from gastroenterology clinics. It's such a protean sort of nonspecific presentation. But if you have someone with chronic malaise and poor appetite and maybe unexplained weight loss, and your GI workup is not really leading you anywhere, it's probably worth thinking about adrenal insufficiency. Even though primary adrenal insufficiency is pretty rare — we're talking cases per millions — secondary adrenal insufficiency is actually fairly common. It's probably worth thinking about and testing for more often than I have in the past. So for me, it's having a lower threshold to start looking for it.

Watto: When it's adrenal crisis, you probably think about it, but then it's too late. Ideally, you would think about it before that happens. But the symptoms can be quite vague. The mineralocorticoid symptoms, like salt cravings, dizziness, near syncope, muscle cramps, might make me think of it because they sound more like something endocrine is going on. But if it's just a little weight loss, a little fatigue, or a little nausea, that's everybody.

Williams: Right. If a patient came to me saying, "I'm craving salt," that might hasten the workup a little bit, but that's not the typical presentation.

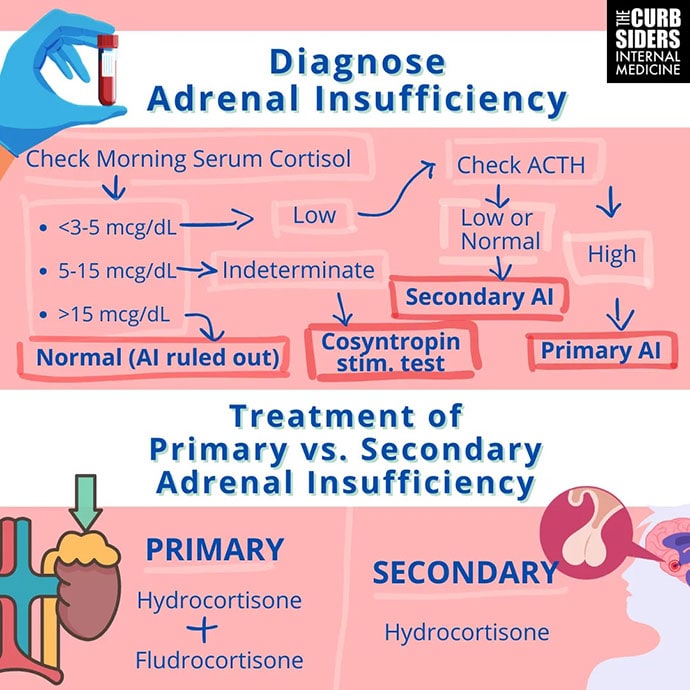

Watto: If you are going to check a cortisol level, you should really check it in the morning, between 7 AM and 9 AM. If you check it too early, it might not have peaked yet, so you might get a level that looks low. But if you had checked an hour or 2 later, it might have been above a threshold, and then you would know you could rule out the diagnosis. The cutoffs depend on your source: < 3-5 µg/dL that early in the morning is pretty much diagnostic of adrenal insufficiency. If it's > 15 µg/dL, that's a pretty robust cortisol and the patient probably doesn't have adrenal insufficiency. But if the level is between 5 µg/dL and 15 µg/dL, you're in a gray zone, and that's where you might think about doing a stimulation (stim) test.

Dr Kargi gave us a quick and dirty version of the stim test. Paul, have you had a chance to try this yet?

Williams: I have not. Have you? I'm sure you've been just waiting for the chance.

Watto: I would love to do this. I don't know whether I'm set up to do it in the office right now. But this is an aspirational goal for my practice, and I'm sure some physicians are set up in their office already to do it. You can give either intramuscular or subcutaneous cosyntropin 250 µg. You don't even have to get a baseline cortisol level right before the injection. Let's say the patient's previous cortisol level was between 5 µg/dL and 15 µg/dL, so you weren't sure about the diagnosis. You bring them back to the office one day, give them a shot of cosyntropin, and then 30-60 minutes later, have a random cortisol drawn. If it's > 19 µg/dL, you've ruled out adrenal insufficiency. If it's anything else, send them to an endocrinologist to sort it out. You might be able to make the diagnosis yourself doing that.

Any treatment pearls to leave the audience with?

Williams: I hope endocrinologists don't take issue with this. I say this with respect and admiration, but it feels kind of vibe-based to me. Without a lab value to guide treatment, you are dependent on the patient telling you how they feel much of the time. You have to let their symptoms guide you. It is probably worth noting that because hydrocortisone has a relatively short half-life, within hours, in fact, you typically have to do twice-daily dosing, sometimes even three times daily dosing to get patients to where they feel okay. It sounds like there's a fair amount of trial and error and some adjustments that you have to make depending on what's going on with the patient at any given time. You land somewhere between a dose of 15-30 mg per day, but there will be some variability, even within an individual patient, depending on what's going on with them from a physiologic standpoint.

Watto: They are going to take one dose in the morning and then a second dose in the afternoon, but they don't want them to take it too late in the evening because it could cause insomnia, and you want to try to mimic physiologic levels as much as you can. Two thirds of the daily dose is given early in the morning and then another third of the daily dose later in the day if you are prescribing two times daily dosing.

And Dr Kargi had a low threshold for doubling the dose. If the patient has a cold, double the dose for 2 or 3 days. With a high fever, triple the dose for a few days. If they are going for surgery, they are probably going to be getting some intravenous hydrocortisone while they're in the hospital.

We really turned over like every stone we could possibly think of on this podcast. There were so many great pearls that we don't have time to go through them all here. But we talked about steroid tapers and a lot more. You can check it out here.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: The Curbsiders

Image 2: The Curbsiders

© 2024 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Matthew F. Watto, Paul N. Williams. Diagnosing Adrenal Insufficiency: The 'Quick and Dirty' Method - Medscape - Jan 02, 2024.

Comments